ACCOUNTING FOR PLANETARY SURVIVAL

ACKNOWLEDG: THE BACKGROUND

Michel Bauwens (org.)

P2P Foundation

michel@p2pfoundation.net

______________________________

Abstract

The proposal of this paper is to present

a summary of ten years of research at the P2P

Foundation, including by our own P2P Lab but also by our partners in common

research programs, of what we know today about the emerging commons economy. It

includes a basic account of why the ‘invention’ of the blockchain has been

important, but stresses that the needed distributed ledgers may take other

forms in the future. This section may not offer a lot of new elements for those

that are already technologically savvy about the topic, but it does offer a critical

engagement with the qualities and flaws of the current model, and suggests how

it can be tweaked and transformed, to also serve as a basis for a

post-capitalist, commons-centric economy.

Keywords: 1. Emerging Commons Economy. 2. Blockchain Technology. 3. Planetary Survival.

Resumo

A proposta deste trabalho é apresentar um resumo de

dez anos de pesquisa na Fundação P2P, inclusive por nosso próprio Laboratório

P2P, mas também por nossos parceiros em programas de pesquisa comuns, sobre o

que sabemos hoje sobre a economia emergente comum. Ele inclui uma descrição

básica do motivo pelo qual a "invenção" do blockchain tem sido

importante, mas enfatiza que os ledgers distribuídos necessários podem assumir

outras formas no futuro. Esta seção pode não oferecer muitos elementos novos

para aqueles que já são especialistas em tecnologia sobre o tópico, mas oferece

um engajamento crítico com as qualidades e falhas do modelo atual, e sugere

como ele pode ser ajustado e transformado, para também servir de base para uma

economia pós-capitalista e economia centrada em bens comuns.

Palavras-chave: 1. Economia Emergente Comum. 2. Tecnologia de Cadeia de Dados. 3. Sobrevivência Planetária.

1

Introduction

1.1 The P2P

Foundation’s study of the commons and the commons transition.

When we

started working as the P2P Foundation in 2006-2007, we started with a basic

premise of what was wrong with the current political economy of capitalism. We

claimed that the system combined strategies of artificial scarcity and

pseudo-abundance in a way that increased social injustice and inequality.

The idea of

pseudo abundance is based on the mistaken premise of infinite material growth

on a finite planet, where natural resources are actually fundamentally limited.

Artificial scarcity refers to the strategies that prevent the sharing of

technological and scientific progress because of too restrictive intellectual

property rights. A sensible alternative is, of course, to recognize the limits

of what we can use from the world of nature, of which we are an intrinsic part,

and to allow for the sharing of all knowledge that can contribute to living

within the limits of this ‘biocapacity’. Right now, we have a production system

where competitiveness is achieved by externalizing human costs to nature and

society as a whole. Capitalism has become a scarcity-engineering machine that

prohibits the occurrence of natural abundance.

From this

beginning, our theory of change was based on the idea that the seed forms of a

new system grow within the old one, usually embedding an alternative logic to

systemic crises.

We would point out that before capitalism became a

fully dominant system, there were inventions like

·

Double entry accounting which focuses on the rational expansion of

private capital (Gleeson-White, 2013);

·

Ideological innovations like the new Catholic concept of Purgatory,

which allow Christians to lend money, while buying back their sins through

indulgences, and which allowed ‘sinful’ commercial activity (Legoff, 1981);

·

The printing press, which allowed for the rapid production and

distribution of knowledge, bypassing the knowledge monopolies of the Church and

the guilds.

These new

patterns and solutions, which created a proto-capitalist sub-system (dominant

at first in the Italian cities and new medieval city-communes) (SPUFFORD,

2002), were paradoxically first used by forces in the dominant feudal society,

such as the monarchy, for their own ends. However due to this allegiance and

investment the seeds of the new system were allowed to grow under the direction

of the "capitalists" themselves. Seed forms emerge and

slowly find each other to form more coherent subsystems- which eventually

become the new dominant norm. This is not a smooth or conflict free process.

Nevertheless, it is important to pay attention to the emerging forces rather

than merely focussing only on the established power structures and conflicts.

Today, this requires making a priority to analysing and supporting

post-capitalist forms of human activity, rather than only pay attention to the

fights for redistribution within the old system, or mere ‘anti-capitalism’ that

is waiting for a ‘final overthrow’ of the system as a whole. These latter

struggles remain an important part of reality, which must be honoured and

understood, but are not creating the necessarily seed forms, though it is

important that forces of resistance also become prefigurative in their demands.

What we propose is to construct seed forms that concretely solve social

and environmental challenges, and a kind of politics that seeks to initiate

policies that can replicate or scale such solutions.

According to

De Angelis (2017), both the commons and social movements are enabling

environments where individual emancipation takes place. They interrelate

insofar as the commons provide alternatives, for which the social movements may

strive. The process of social revolutions necessitates an alignment of commons

with social movements, synchronizing their respective sequences “to turn the subjects

of movements into commoners and make commoners protestors” (DE ANGELIS, 2017,

p. 371). They thus become mutually reinforcing, through the expansion of the

commons, which in turn forms a new basis for more powerful movements.

Commons-Based Peer Production (CBPP) then serves as a driving force for the

material recomposition of the commons. It enables the conditions to sustain

livelihoods for the commoners and the deployment of social force to reconfigure

their relations to the current social systems, including capital and the state.

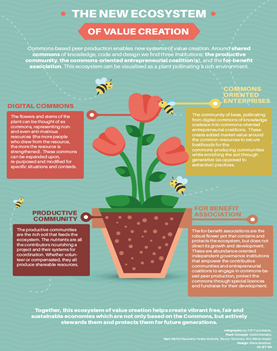

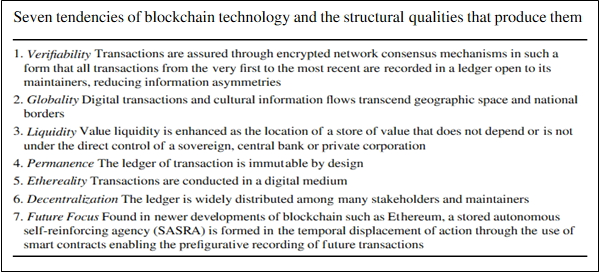

We also claim

that the emerging new world-system would be commons-centric, and that the

existing state and capitalist market forms would be transformed under the new

‘dominant’ logic of the commons. What we saw emerging was a new mode of

production and exchange, where communities create shared value through open

contributory systems, govern their common work through participatory practices,

and create shared resources that can, in turn, be used in new iterations. This

cycle of open input, participatory process and commons-oriented output is a

cycle of accumulation of the commons, in contrast to a capital

accumulation. This mode of production, which Benkler (2006), called

"commons-based peer production”, thrives in ecosystems comprising 1)

contributory communities, sharing knowledge and capacities; 2) entrepreneurial

coalitions creating livelihoods around the commons; and 3) for-benefit

infrastructural organizations, which support and guarantee cooperation in the

ecosystem, allowing it to continue over time.

Before this

becomes a new form of civilization, it appears as new hybrid eco-systems in

which post-capitalist seed forms exist within a framework dominated by the old

forces. This understanding imposes a double priority on our work as activist

researchers: first of all to document the emergence of these seed forms, as

they are adapted and used by the current dominant forces, for their own

survival and benefit, but also to look at how we can strengthen and create more

autonomy for these commons-based productive communities. Our strategy is to

identify, understand and promote the commons-centric, post-capitalist logics

present in these emerging new forms. In the commons economy

that we see emerging and want to strengthen, we see value created by open

productive communities, translated into material resources for ‘social

reproduction’ and livelihoods through ethical and generative enterprises, with

the common infrastructures maintained by democratic foundations bringing the various

stakeholders together in dialog, to jointly manage the common infrastructure.

A very

important distinction for us is that between extractive and generative

practices, and the institutional and ownership forms that enable it

(KELLY, 2012). For example, every year a farmer practices industrial and toxic

agriculture, the soil is impoverished, until it becomes exhausted for farming,

but every year an organic and biodiverse farmer works on the land, the land

enriches. The first mode is extractive, the second mode is generative from the point of view

of the soil. Extractive are for example the companies in the most often

mis-named ‘sharing’ economy. While Uber and AirBNB scaled up the necessary

mechanisms for ‘idle-sourcing’ (i.e. allowing the re-use of idle resources),

they are socially extractive, destroying social welfare standards, creating

precarity and insecurity etc. The key issue addressed in this study is how to

change a system which incentivizes and rewards extraction and dispossession, but cannot recognize and reward the wealth created by generative

activities, towards a system which can reward and incentivize generative

practices. Furthermore, we are looking for generative practices that are

embedded inside the productive system itself, and do not have to be imposed on

it from the outside. Our current system is extractive towards nature and human

beings and seeks for corrective measures ‘after the fact’.

What we need are productive systems that are ‘organically’ or

‘institutionally’ generative.

Figure 1 - Value creation in the commons economy

Source: P2P Foudation.

In today’s context, we see on

the one hand that the traditional, natural-resource based commons identified by

Elinor Ostrom are under stress by the development of capitalism, while, on the

other hand, we observe the growth of new types of commons. For example, we have

seen the rapid emergence and growth of open source communities, co-producing

shared knowledge, software and design. After the crisis of 2008, this was

followed by the emergence of the platform economy, which brings supply and

demand together in corporate owned platforms, but also the emergence of

alternative platform cooperatives that are co-owned and/or co-governed by their

stakeholder communities. And as the crisis was felt concretely in the cities

where most people now live, we saw the emergence of urban commons, where

commoners start taking the infrastructures for provisioning into their own

hands. In our study of the city of Ghent, we saw an exponential growth of

urban commons, in every area of human provisioning, i.e. food, mobility,

habitat etc. However, except for the sectors of organic food and distributed

energy, which have highly developed ecosystems with commons-centric forms of

organization, most of these urban commons pertain to a different distribution

of the goods and services, not to the production of them. Nevertheless, the two

latter examples point to a future where physical production itself could become

commons-centric in its organization.

It is important to see what

we are already capable of doing in terms of our techno-social capacities:

1. Open source communities are able to scale small-group dynamics by

interconnecting tens of thousands of individuals and small groups, as well as

larger groups, into large eco-systems for open coordination through

‘stigmergy’, i.e. coordination through signalling, by relying on open and

transparent systems; the creation of shared knowledge (Wikipedia), shared

software (Linux), and shared design (Arduino), already operates that way.

2. Platforms allow for the easy exchange of idle objects and

services, using massive person-to-person interaction on a global basis.

3. Urban commons communities are able to organize access to resources

that are more equitable and ecologically responsible.

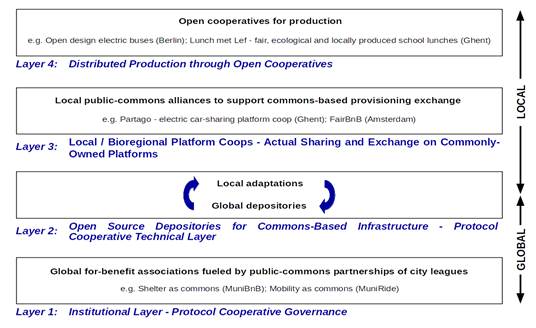

The next step in the

evolution of the ongoing transition to commons-centric ways of producing and

distributing value is therefore ‘physical production’ itself. The central

concept of the P2P Foundation in this context is ‘cosmo-local production’

or DGML: design global, manufacture local.

This means that the technical, social and scientific knowledge needed to

organize production is available through global open design communities, but

that a large part of production for human needs can be relocalized through

distributed manufacturing. What we favour is the subsidiarity

of material production, i.e. to produce to minimize the huge costs of

transportation currently necessary under neoliberal globalization. In this new

model, ‘economies of scale’, i.e. bringing down the costs of production per

unit by a massive scaling up of productive capacity through centralization,

which necessitates ever more natural resources and transportation, are replaced

by economies of scope, i.e. making global knowledge and

innovation instantly available to all nodes of the network, which can then

apply circular economies, biodegradable materials, and more, to produce more

directly for local need, as these needs emerge, without necessitating constant

over-production and the constant promotion of over-consumption. With economies

of scope, the object of production becomes, ‘doing more with less’, creating

value through variety, rather than through volume.

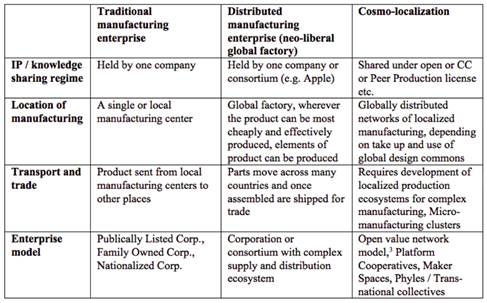

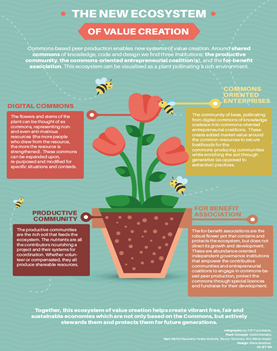

Figure 2

- Cosmo-local production

Source: P2P Foundation.

The socio-technical requirements for this shift are essentially

the following:

·

We need open and shared supply chains to instantiate a

perma-circular economy, so that all the players in the

ecosystem can plan and coordinate their production and distribution activities.

The circular economy refers to ‘circular’ production systems, where the output

of one process, becomes the input for another, thereby drastically reducing

waste. The ‘perma’ qualifier refers to the need to stabilize the growth of our

usage of matter and energy so as to to make these processes sustainable over

the long term. The limit to material growth has been calculated to be a

maximally one percent per year;

·

We need shared accounting systems and distributed ‘ecosystemic’

ledgers, so that value streams can be exchanged. These systems need to allow

permissionless contributions and need to reward these contributions in a fair

way. Open and contributive accounting will be discussed in chapter x;

·

The open and shared accounting systems also need to reflect a

integrated or ‘holistic’ knowledge of the actual ‘metabolic streams’, i.e.

thermo-dynamic flows of matter and energy, and create a context-based

sustainability for all the players in the ecosystem. What this means is that

the limits to the usage of resources, should be directly visible in the

ecosystems that create and distribute the particular product and service.

Solutions for this will be discussed in our third chapter. As James Gien Wong

explains: “Here we have the concept of localizing planetary boundaries down to

a granular level. There should be thresholds that signal that a value exchange

is coming close to exceeding a regional boundary. We need to have multi-scale

setpoints that alert us that we are within acceptable ecological footprint

boundaries”.

The aim

of this study is to offer an overview and synthesis of the seed forms that are

emerging to make this a real possibility in the coming decades. The concepts,

prototypes, experimentations and actual practices already exist, i.e. many of

the seed forms have been developed, but they are as yet fragmented, and have

not yet created generative ecosystems, with some exceptions.

The next

step of creating such budding ecosystems requires paying attention to the

technical systems being developed as we speak, for example the extraordinary

developments around the deployment of distributed ledgers for shared accounting

and coordination of production. The key issue that needs to be solved in order

to achieve truly sustainable production for human needs, is whether what we produce

is compatible with the survival of our planet and its beings. Equally

necessary, is to pay attention to the value distribution. Indeed, most models

developed today involve using open source and the commons to develop highly

unequal extractive capitalist market forms, and do not use generative market

forms that would help strengthen the autonomy of the commons and the commoners.

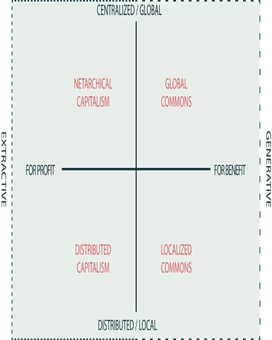

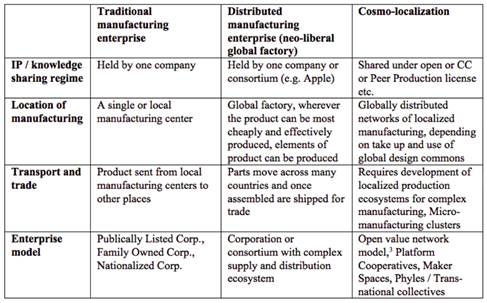

Technology

is of course not neutral, since its design reflects human intentions, material

interests, and a balance of power between developers, funders, users etc. We

have a four-quadrant model to explain this value-driven design of technology.

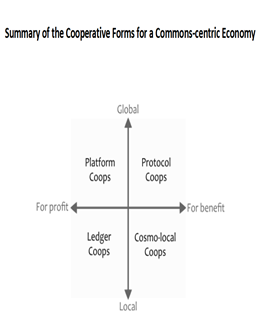

Figure 3 - P2P socio-technical dynamics and cooperative forms: 2

pictures

Picture 1 Picture

2

A first model involves enabling p2p

behaviours (both commoning and p2p-forms of market exchange) through centrally

owned and controlled corporate platforms, think Facebook/Google,

Uber/AirBNB as models for this. This model, which also includes state actors

that aim to control internet communication and platforms, could be called

Leviathan, since it is about surveillance, the control and nudging of human

behaviour, and the capture of value from commoners.

The second model, which is the one that

will be discussed mostly in this study, is the model of distributed capitalism.

These are formally decentralized systems that aim to create permissionless

usage by avoiding centralized gatekeepers (we will amend this over-simplification

later on). We call this model Mammon, as the aim is, despite the usage of

open source technologies and commons of code, to extract profits.

The third model involves

creating commons for local provisioning, this is the dominant model amongst

urban commons, but that do not aim for profit-maximisation. Enzio Manzini has

characterized these models as ‘SLOC’, for Small, Local, Open, and

Connected. This model can share global knowledge over common platform, but

still aim to operate locally, i.e the global serves the local.

Finally, there is a fourth model, based

on global open design communities that aim to create global common goods and

are organized beyond the local. In this model, the global is recognized as a

priority in its own right. These projects are often managed by non-profit and

democratically run foundations, but as yet to rarely surrounded by

not-for-profit entrepreneurial coalitions.

For the third and fourth model, we often

use the name of Gaia, the Greek Goddess of the Earth, since these projects are

most often geared towards sustainability. The third model is specifically

“generative” in its orientation towards local communities and ecological and

social goals. In the fourth model, the ecosystems are generative towards the

creation of global common goods that are universally available.

This means that we are not merely

discussing competing models and platforms in the name of efficiency or

profitability, but also worldviews, with different social and political

priorities.

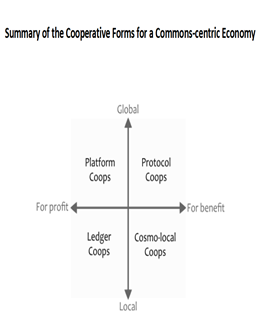

In the context of the P2P Foundation’s own views,

this means that we look at how to transform the functions of the central

corporate platforms, into platform cooperatives and open cooperatives that do not merely capture the

value created by their users, but can be co-owned and co-governed by their

stakeholder communities. In the case of the infrastructures of distributed

capitalism, such as the blockchain, this means we will look how to tweak and

transform them, so they can be used to serve for the expansion of a socially

equitable and ecologically regenerative model of production for human needs,

serving the needs and interests of the commoners. In this context, we explore

the concept of ledger coops. The third quadrant

calls for urban provisioning coops and in the fourth, generative global

quadrant, we call for ‘Protocol Cooperatives’. A protocol coop is basically a

governance form for global open design depositories, collectively managed hubs

of software to assist in the deployment of local systems for the mutualization

of provisioning systems. In this scenario, leagues of cities could, with

other allies, cooperate in the setting up of such common infrastructures, say

in order to replace the extractive models of AirBnB, with generative models

such as FairBnB, thereby avoiding duplication of effort. Please note that we

use the concept of ‘cooperative’ in a generic way here, to indicate all institutional forms that are not

geared towards profit-maximisation but to generative purposes.

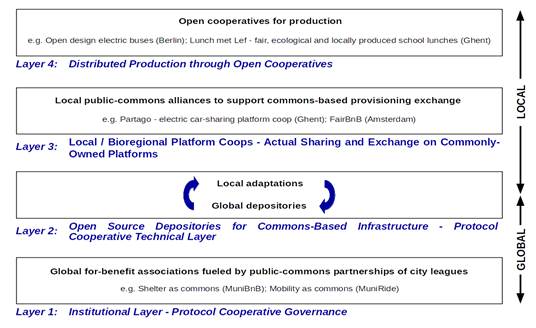

Figure

4 - City-supported

cosmo-local production infrastructure

The first law, of the conservation of

matter and energy, states that no matter/energy can get lost, only transformed.

This can be linked to the development of the idea of liberalism and the

generalisation of support for growth-oriented capitalism, i.e. an economic

system based on the idea of material abundance and infinite growth, since

indeed, nothing can be lost.

The second law, on the dissipation of

energy from high levels of order to lower levers of order, i.e. entropy,

introduces the idea of scarcity, and a demand that basic needs should be

covered, before they are unequally distributed. This new insight could be seen

as reflected in the socialist aims of the labour movement.

But as Yochai Benkler (BENKLER, 2011),

and others have described, there has been for the last few decades a much deeper

appreciation of how human (and other forms of cooperation by living beings)

cooperation and synergy leads to neg-entropic effects. This means that life and

society create temporal and territorial exceptions to entropy and lead to

domains where order and complexity increase over time. (Some have argued this

should be construed as a third law. The new generations of technology should

reflect this understanding and become eco-systemic and ecological in their

approaches to producing and distributing value. This is only happening

partially, in that our emerging systems apply are becoming eco-systemic but not

yet truly ecological.

The next two sections outline what we

have discovered about value streams in the commons economy and introduce the

issue of externalities.

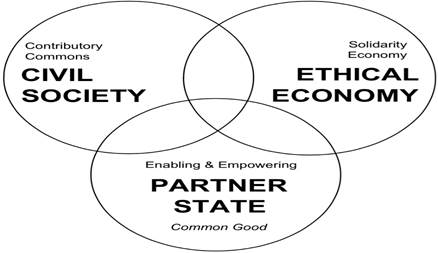

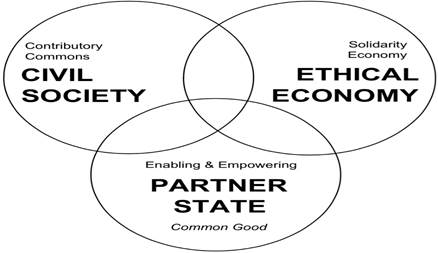

Figure

5 - The three great spheres of

social life in commons transition

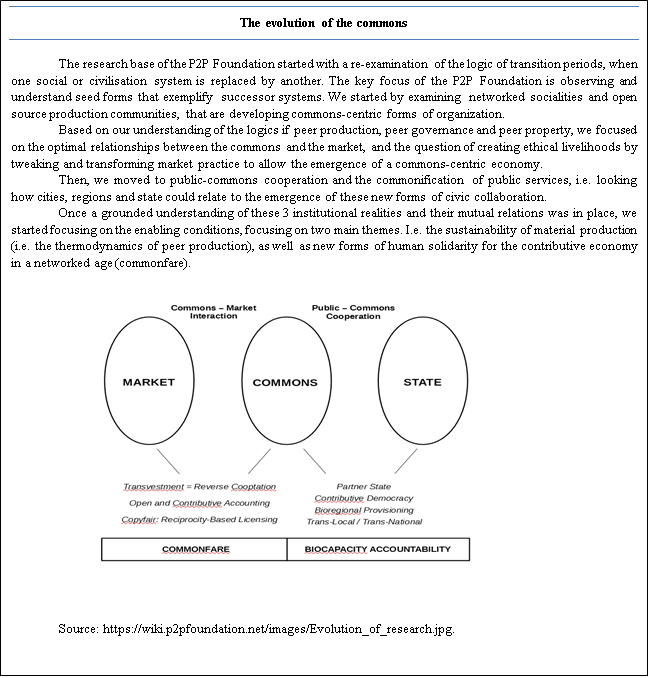

Box 1- The evolution of the commons

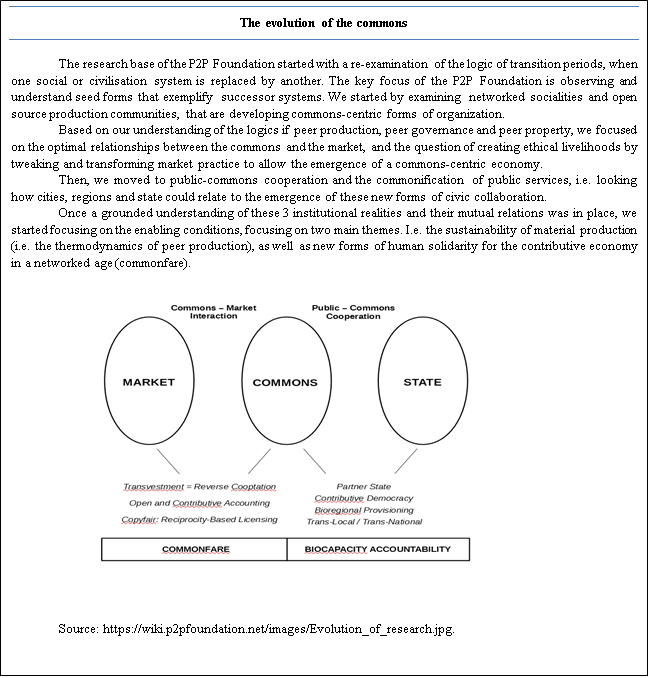

Box 2 – The evolution of research in the P2P

Founation

2 VALUE IN

THE COMMONS.

This report

builds on the previous findings from earlier research reports. The P2P Value

research project had shown that a majority of the 300

peer production projects that had been studied were engaged in using,

prototyping or experimenting with contributive accounting, i.e. forms of

accounting not based on hourly labor but recognizing all other manners of

contributions in these open and permissionless production communities.

Our study,

Value in the Commons Economy, based on different case studies of advanced peer

production communities such as Enspiral and Sensorica, outlined the following

concepts and practices:

- The

new peer production communities are directly oriented to the production of

use value, not exchange value, and make claims to ‘value sovereignty’,

i.e. the right to determine context-based value regimes that differ from

the sole recognition of commercial value under capitalism. This allows for

a autonomous flow of value within the communities and for the recognition

of all kinds of contributions, not just paid ‘commodified labour’.

- These

new communities create a membrane between the commons and the market,

which allow them to regulate the flows of value between income from the

market and state-based value models, and the internal flow within the

commons, which can be differentiated from each other, in other words, it

is possible to accept revenue from outside the commons, but to distribute

according to the norms of a particular commons.

- We

recognized three models: one in which the commons and the market are

clearly demarcated, allowing free unpaid contributions and free usage

within the commons, which is thereby protected against contamination by

market exchange logics; a second model in which contributions are rewarded

by a different value equation; which are then funded post-hoc by income

from the market and the state; and finally a third one that more

intimately and directly links commons contributions to market income.

- These

communities practice and experiment with reverse cooptation of market

income and investments, i.e. ‘transvestment’.

While investment concerns using capital to obtain more capital,

transvestment uses market and state investments, but translates them into

the growth of commons assets and infrastructures. For example, capital is

attracted and even remunerated, but increases the common stock of free

software, or commonly-owned land in a land trust, etc. One of the

techniques is to create a wall between investments and the purpose-driven

generative entities creating livelihoods for the commoners.

- A

few are experimenting with new forms of licensing, halfway between the

‘free-for-all’ copyleft licenses and the privatizing copyright licensing

models. In copyfair models, the sharing of knowledge remains entirely

free, but commercialization is conditioned by some forms of required

reciprocity with the commons.

A landmark

study for us has been our research publication about the ‘Thermodynamics of

Peer Production’. In this study, we show the vital

impact of mutualization of infrastructures of production and consumption, to

the lowering of the footprint of humanity, which is already visible in the

local commons-centric food economy for example. Sharing resources, for example

in car-sharing that follows non-profit or cooperative modalities (but NOT using

models like Uber, which augment resource use), every shared car can replace

from 5 to 15 private cars, dramatically reducing the needs for

matter and energy expenditure.

This

advantage were confirmed in our study of the urban commons in Ghent, where we

were able to determine that, for every single provisioning system in the city,

there are now no longer just choices between private and public models (say

private housing vs state-sponsored social housing), but also commons-based

alternatives (such as commons-based cooperative housing modalities). Various

studies have confirmed, at least for car-sharing, that this type of

mutualization effectively overcomes the Jevons Paradox, which states that

lowering cost and efficiency often leads to higher consumption. Our challenge

is to place the advantages of mutualization in lowering the human footprint in

a sufficiently systemic change effort, so that gains in one sector are not

undone by higher consumption in other sectors.

We cannot

stress this enough: putting commons center stage, i.e. shared resources

self-managed by their stakeholder communities, is a vital necessity in any

social and ecological transition. This is confirmed by the HANDY study,

which compares the resource crisis moments of hundreds of past civilizations,

starting from the neolithic period. Far from being exceptional, HANDY

shows that civilizational collapses are a regular occurence in class-based

societies, where ruling classes are perforce engaged in competition with their

peers, and driven by this necessity, over-use their local resource base to the

point of collapse.

The study

shows that inequality is a vital part of accelerating and deepening such

collapses: the more unequal the society, the more egregious the over-use, the

deeper the fall, and the longer it takes to recover. Equality mitigates these crises

and can perhaps even avoid them. Mark Whitaker has produced a comparative study of

more recent collapses and resets in China, Japan, and Europe, and has shown the

vital role of mutualization in the revival of these societies. Notice the

parallel between the role of pan-european exchange of knowledge by christian

monastic communities, the mutualization of their production infrastructures in

the monasteries, and the relocalization of production in the feudal domains, with

the current emerging reactions: the creation of vast open source and open

design communities, new forms of mutualizations of infrastructures in the

models of coworking and makerspaces, as well as the ‘sharing economy’, and the

increasing experimentation with cosmo-local models of distributed

manufacturing.

An important

part of any systemic change are changing class dynamics and structures within

society. The shift from the Roman system, based on conquest and slavery, to the

feudal system, based on local production in local territory, was a shift from

slavery to serfdom and from slave-holding to feudal status. The shift from feudalism to capitalism was a

shift from serfdom to working in factories. From land ownership to ownership of

investment and financial capital.

In our

analysis, the current shift involves a shift towards netarchical capitalism,

i.e. the direct exploitation and capture of value, not from commodity labour in

factories and offices, but from peer to peer exchange in platforms and from participating

in commons-based peer production. In other words, the new capitalism is a

commons-extracting capitalism, which directly enables, but also exploits, human

cooperation. One could say that we have evolved

from a Marxian capitalism, with surplus value directly extracted from labour as

a commodity, to a Proudhonian capitalism, since the latter argued that surplus

value was derived from the extra value generated by human cooperation.

In this

particular conjuncture, we see the increasingly larger parts of the working

class is evolving, at least in western countries, from a subordinate

salariat to a condition of generalized precarity (some call it ‘the precariat’)

(STANDING, 2011), but which also involves the growth

of post-subordinate autonomous workers who are simultaneously involved in

networks, commons, and markets. These workers need to participate

in networks to create connections, expertise and reputational capital, and are

often passionately involved in contribution-based and permissionless digital

commons; but they often operate as freelancers in the market. They often have a

strong desire and demand for autonomy and free cooperation. In many ways, this

‘cognitive working class’ is at the forefront of social change today, becoming

an active agent in the transformation in the system, largely thanks to their

vital place in the knowledge ecosystem. This is evident in the growth of open

source economies tied to the urban commons and other areas beyond what is

usually perceived as "knowledge work". In this report we will

concentrate on the growth of systems of production and distribution of value

using distributed ledgers, or what is now known as the blockchain or crypto

economy.

For the

last year, one of the authors has been closely involved with a large European

platform cooperative, SMart (coop), which is also called a labour mutual. In a

labour mutual, formally independent workers, who in the best of cases have a

passionate life project that allows them to filter their work engagements, are

able to create solidarity, by converting their invoices into salaries, and

thereby gaining access to the social protections of the welfare state.

These autonomous, post-subordinate workers also represent a convergence

model between the precariat and the salariat, and are prime candidates for the

emerging commons economy, they have a big role in the creation of the

post-corporate eco-systems that we will be describing in one of the chapters of

this report. Please note that we do not see these new types of workers as the

sole actors in transformation, but we do believe they play a very important

role in this particular transition. To the degree that the labouring classes

start to see themselves not as merely adversarial to the current system, but as

active commoners in the creation of new life forms, to that degree they are

also joining the new commoner or ‘hacker class’.

Box 3 - The role of labour mutuals, commonfare and

post-subordinate workers

3 THE EMERGING CRYPTO ECONOMY AS A SIGNPOST FOR THE COSMO-LOCAL

TRANSITION.

If

we look at the evolution of contemporary commons, from the emergence of the

immaterial ‘digital’ commons for knowledge, software and design, via the mostly

redistributive provisioning systems of the urban commons, we now see the

emergence of a new phase that involves bringing the use of the open source and

commons models, straight into the physical production processes. For example,

the Economic Space Agency speaks of a shift from open source software

production methodologies, to open source economic spaces, i.e. from the mere

production of knowledge, code and design, to full-scale economic cooperation

around the production and distribution of all kinds of value, so as to secure

livelihoods.

The

emergence of the distributed Bitcoin currency, and most importantly its

underlying infrastructure broadly discussed as blockchain technology, is a very

important signpost for this, as we explain further in this document. In this

chapter, we aim to provide a short explanation of this emergence, critique the

current models from a P2P and commons-based point of view, so that we can

suggest the main tweaks and transformations that are necessary for the support

of a true, solidly commons-oriented mode of production and exchange in the

sphere of physical production. This would combine our priorities for open and

freely shared knowledge, respect for the biocapacity of the planet, and fair

distribution of the rewards for common work.

The aim of

this work is to see how we can ‘internalize’ in our management of the

production and distribution of value what is presently ‘externalized’, i.e. not

accounted for and not cared for.

The design,

emergence and success of Bitcoin was a very important first pivot. Over the

last decade there has been an increasing number

of locally based complementary currencies, but with limited numbers of local

users and turnover. To date, they very rarely achieve scale even in their local

contexts. By contrast, Bitcoin was the first

attempt for a globally scalable currency that was based on social sovereignty,

instead of corporate or state-based sovereignty.

The trust of the community was ensured, not by mediating third party

institutions but by trust in the integrity of cryptographic rules. For

the first time in recent history, we have a currency that was created

autonomously, and gained the trust of a global community, while achieving

tangible and spectacularly recognized levels of market value. Following Bitcoin,

many other cryptocurrencies are also achieving relative success, even amid the

speculative frenzy. We can observe a surge of permissionless creation of

currencies, with a relatively autonomous capacity to allow value flow outside

of the traditional banking channels, which gave rise to the idea of

crypto-assets. These value flows are coordinated in more decentralized ways,

even if new types of intermediaries may be facilitating this. Cryptocurrencies

have thus been envisioned as a store of value, and a kind of global reserve

backing, like gold, but their usability in day-to-day exchanges in real

marketplaces has not been realized, except very marginally. At any rate,

crypto-currencies introduce the idea of pluralist value streams and the

circulation of assets in decentralized P2P networks.

However, even

if the Bitcoin code is open source and supported by a global community, there

are also huge issues that do not make it an appropriate currency for the

commons economy. Essentially, the commons are subsumed here to social and

ecological extraction. Social extraction, because the particular design means

that early entrants can sell bitcoins at a higher price later (because

production is designed to slow down and even stop over time, while demand grows

without set limits, thereby structurally stimulating demand over supply)

and this has made bitcoin into a tool for financial speculation.

And ecological extraction, since its production necessitates exponential energy

usage.

Value in

Bitcoin is created through the monetary mechanism itself, not by the creation

of productive value. In fact, Bitcoins are created through an extremely

resource-intensive process called “mining”, which is very capital and resource

intensive, as it requires huge computational capacity. Bitcoin thus relies

essentially on capitalist mechanisms for its existence. Furthermore, almost the

entirety of Bitcoin mining has gradually been taken over by vast mining plants,

specially designed to afford enormous processing power, making it almost

impossible for single users to engage in any mining themselves.

Hence, Bitcoins for them can only be acquired in exchanges, again via the

capitalist market (or by working for the owners).

Most

cryptocurrencies are traded as financial assets on open markets, i.e. their

price is based on supply and demand, and is denominated in regular fiat

currency. Value flows from one currency into another, but the currency is a

representation, that does not create value by itself any more than a balloon

creates ‘volume’. In other words, Bitcoin owners extract rent from productive

value creators in the rest of the economy, it is a distribution of rent-seeking.

Bitcoin is most certainly a currency of and for the market, more specifically a

currency for decentralized capitalist market dynamics, specifically for market

forms that seek to escape governmental and societal control.

Beyond

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, a second generation of blockchains

introduced autonomously executed computer processes broadly known as “smart

contracts”. These are software programmes stored on a blockchain and employ a

set of pre-defined rules that may be enforced automatically once certain

conditions are met. Multiple parties in a distributed network can access and

interact with smart contracts, but they are largely autonomous and very

difficult to reverse once deployed.

Ethereum was

the first initiative supporting the deployment of smart contracts on a

blockchain. It envisioned a potential use of blockchains that goes beyond

the storage or reference of transactions, but may include any type of

information that allows users to define the functionality of decentralized

applications (dapps). Ethereum also implements its native crypto-currency

called “Ether” that, much like Bitcoin, is allocated to miners through a

similar process and can be transferred in the network.

Smart

contracts gave rise to an ever-increasing number of potential uses of

blockchains, on every domain where formal agreements have to be encoded and

enacted, including financial transactions, insurance and securities, and

intellectual property rules. Probably the most ambitious deployment of smart

contracts has been new types of decentralised organisations, commonly referred

as “Decentralized Autonomous Organizations” (DAOs), which rely purely on

blockchain code and the distribution of tokens to enforce their rules to

control decision making and operations. The DAOs have stimulated discussions

and experiments around the provisioning of digital services and transactions that

take place with little or no direct human action, while they arguably cede

agency to non-human subjects, including machines, objects or even natural

ecosystems.

It

is especially in this light that the blockchain, or more broadly ‘Distributed

Ledger Technology’ (DLT) has been acknowledged as an even more radical

innovation. We note that accounting and civilization have developed together.

Writing was invented as a by-product of accounting, when temple-state,

class-based civilizations emerged in Mesopotamia, to keep track of the coming

and going of commodities in the temple storage paces, as well to record debts.

These first forms of accounting accompanied the birth of class-based

civilization and the accompanying state forms. When the Franciscan monk Pacioli

standardized ‘double entry’ Venetian bookkeeping in the year 1494,

it announced the birth of capital accumulation which would eventually engulf

the whole world a few centuries later. Today, next-generation accounting

models, such as Resources - Events - Agents abandon double-entry to

favor

ecosystem-

and network-based accounting flows. What we get is something that goes beyond

closed corporate accounting and potentially announces and accompanies a huge

civilizational shift away from atomized institutions that compete with each

other, and instead points towards a more networked structure based on much

higher levels of collaboration over joint platforms.

The

blockchain encodes and shows the viability of open and shared accounting in

representing the multitude of transactions and actions occurring during

physical production.

This is

historic, as this allows us to move from corporate and nation-state accounting,

(which even as they are publicly regulated and accessible to the public,

are ‘privative’ accounting internal to bounded entities, in which

externalities are invisible), to ecosystemic accounting in networks with

multiple participants and in an environment of permissionless contributions. In

other words, it allows for large-scale mutual coordination of physical

production, and makes practical the scaling of circular economies. It is an

extension of the principles of the open source economy, to physical production.

Distributed

ledgers furthermore allow both the recognition of a variety of contributions,

i.e. open and contributive accounting, but also the capacity to integrate

directly the visioning and management of physical flows of matter and energy.

This differs from the previous approaches such as Ecological Economics, that

converted resources in price signals. The

combination of distributed and shared ledgers, as well as the capacity to

integrate externalities, constitute a radical innovation

Presently,

the production of immaterial value, i.e. knowledge, software and design, enables

‘stigmergic coordination’ between permissionless contributors,

who can access open and transparent depositories that represent the flow of

work. With shared accounting, this capacity for mutual coordination moves to

the physical plane. But because physical production requires specific

reciprocity in terms of material capital (which otherwise would get depleted),

and not just the principle of free universal usage, it requires that

distributed ledgers add this layer of value exchange.

To use the

19th century language, for example as used by Marx:

- As far as

immaterial production is concerned, we already have the principle of

‘communism’ at work in the very heart of the capitalist economy (in its

original sense of ‘everyone can freely contribute and everyone can freely

use’), which some authors like Richard Barbrook have called

cyber-communism (or ‘cybernetic communism’, BARBROOK, 2015),

because of the ‘abundance’ of digital knowledge which is easily and

cheaply reproducible, and thereby overwhelms the scarcity dynamics of

supply and demand, moving the market functions to the periphery of open

source production communities, with the commons in the middle.

Paradoxically, this cooperative coordination is largely incorporated in

the corporate economy, inspiring some scholars to speak of the ‘communism

of capital’ (BAUWENS; KOSTAKIS,

2014).

- In

physical production however, we need reciprocal flows, to avoid depletion

of non-renewable resources, either through market exchange (but not

necessarily capitalist exchange) or through contributory recognition (‘to

each according to his/her contribution’, this was defined by Marx as

‘socialism’). Capitalist markets are

nominally based on the idea of equal exchange, but in their actual

practice they are based on the constant extraction of surplus, from nature

and other humans, in order to accumulate capital in private hands.

Ethical and

generative markets use monetary signals, but are not focused on profit

maximisation. Many pre-capitalist markets were socially embedded, as Karl

Polanyi has shown. We will later show that we need to move from pricing

signals, which reflect current supply and demand, but not the necessities of

protecting and maintaining resources in the long term, to monetary signals,

i.e. to currencies that are directly related to the status of the natural

resources we need to maintain and replenish. If such a linkage between the

amount of natural reserves that are sustainably available, and a corresponding

monetary mass could be achieved then the monetary signals themselves would be a

technique for responsible material production. An example of this is the Fishcoin

project, in which the amount of coins that can be spent reflect the stock of

fish that can be used without endangering the reproduction of the fish.

So, the

blockchain, like Bitcoin, has received extensive attention and a huge wave of

investments, viewing it as a new infrastructure layer for a more distributed

economy. And precisely because it is linked to the design philosophy of

Bitcoin, it shares some of its fundamental limitations. The design of Bitcoin

and its infrastructure are based on an individualistic understanding of the

economy, that combines elements from the marginalist traditions, Austrian

Economics’ and an ‘anarcho-capitalist’, ‘propertarian’ philosophy. It is

based on ‘methodological individualism’, the premise that society consists

of individuals seeking maximum advantages in a competitive game. Every human

being is seen as an entrepreneur, which contracts with others in order to

conduct his or her business.

For example,

when blockchain projects talk about governance and ‘consensus’, what they

emphatically don’t mean is collective governance based on democratic

deliberation, but merely the coordination of individual actions with common

intentions. Because liberalism believes that

the common good results from individual and corporate competition, it has no

clear concept to articulate it other than the accumulation of individual gains,

and it does not see the inter-dependence of the market to a whole host of

societal and environmental realities. The commons and open source dynamics are

often appropriated to emphasize individual freedom, mostly restrained to a ‘one

dollar, one vote’ context, disregarding the elements of social fairness and

ecological sustainability.

As Arthur

Brock has argued, there are no people and communities in the blockchain design,

no community governance, ‘only transactions organized in blocks linked to a

chain’; there is no organic connection

between the blockchain and the open source communities and commons that

undergird it.

Furthermore,

bitcoin and blockchain are not truly distributed, i.e. consisting of equipotent

peers that voluntarily create nodes through their free and open cooperation,

but rather decentralized. This means that while it avoids the domination by

vertically integrated oligarchic companies, it is still based on major power

blocks, such as influential ‘miners’, large investors, etc. Bitcoin’s

inequality coefficient, measured by the Gini metric, is

higher than the inequality in the sovereign currencies that it aims to replace.

Blockchain has an oligarchic design, as most mechanisms used to reward

contributions (the ‘proof of work’ mechanism) and resources (the ‘proof of

stake’ mechanism), reward those that can already provide the most.

Sam Pospischil writes:

[…] blockchains are too slow and expensive for

a large variety of use-cases. If you look at something like, say, OriginTrail,

they've built a separate overlay network to store structured graph data and

document attachments. Pretty much everyone has something similar, with varying

levels of "decentralised-ness" ranging from traditional SQL databases

to networks that anyone can spin up and participate in just like a (public)

blockchain.

Different layers of the blockchain ecosystem are routinely dominated by

a small group of dominant players, even if they have to content with the other

layers in the system, miners, developers, users.

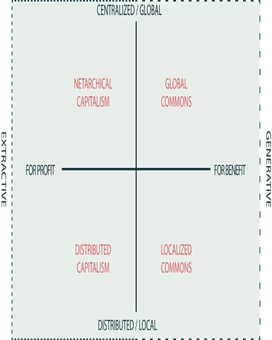

What matters in this report therefore, is not necessarily the blockchain

in the narrow sense, but the generic concept of distributed ledgers. Nevertheless,

it would be a mistake to underestimate the innovative features of the

blockchain design, which Sarah Manski has summarized.

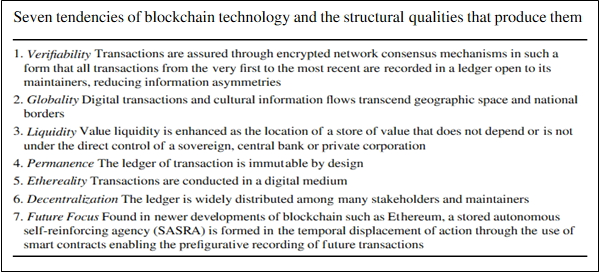

Box

4 - The seven tendencies of blockchain technology by Sarah Manski

Sarah Manski has also analyzed the underlying

political visions of the blockchain designs, resulting in five possible futures:

·

The first is the individualist future, based on

anarcho-capitalist visions of the world, in which every individual is seen as a

competitive entrepreneur;

·

the second is the corporate vision, which can

use ledgers for a variety of for-profit and procontrol-base uses;

·

the third is the vision of particular state

forms with a desire for control and surveillance,

·

the fourth is the technocratic future,

expressing the fear that such technologies can become automatic and sovereign,

beyond human control.

·

But the fifth one is the cooperative future, in

which distributed ledgers are used for the commons. This is the vision that animates this report.

Rachel O’Dwyer also provides an extra warning: if we design distributed

ledgers following the values and processes of ‘methodological individualism’,

then we also end up generalizing and socially reproducing these neoliberal

mechanisms. As Salvatore

Iaconesi warned, distributed ledgers may end up transactionalizing our entire

lives (scenario 1 and 2

from Manski).

At the very least though, the new distributed capitalism can create more

capacities for what Adam Arvidsson (Arvidsson, forthcoming 2019), following

Giovanni Arrighi (ARRIGHI, 2009), call ‘industrious capitalism’ (or rather,

‘industrious modernity’, as it can also be non-capitalist).

This is a vision of capitalism and markets seen in the context of a ‘class

struggle’ for markets, whereby workers and a multitude of small firms use

market forms to their own benefit, until today mostly in rather invisible

informal economies. Distributed capitalism may put these forms on steroids.

The

interesting White Paper by Outlier Ventures, a venture capitalist firm founded

by Jamie Burke which exclusively invests in ‘decentralized infrastructures’ is

very illustrative on the proposed relationship between open source commons, in

the form of blockchains and tokens, and how it fits in a new vision for

capitalism. Their paper on Community Token Economies

argues that ‘siloed innovation’ is inherently wasteful, on the one hand because

of its endless duplication in the creation of common infrastructures, but also

because, in case of failure, which is the norm rather than the exception,

valuable innovation is lost each time the Intellectual Property is lost.

Therefore, businesses must massively mutualize their common infrastructures,

and community tokens serve to align the various stakeholders, while also

providing a funding mechanism for open source developments. While there is a

obvious call for more inclusion and fairness in the ecosystem through decentralization,

there is no questioning of the primacy of profit maximisation. Thus, blockchain

capitalism is indeed a new form of capitalism, in which the commons are

embraced, but also to a large degree instrumentalized.

4 OUR VISION

We stand for a different vision.

First, we

want to make these distributed networks truly cooperative, much more

egalitarian, and sustainable, i.e. we want to:

·

Embed different values in the design of the

shared ledgers, such as through replacing the blockchain with the holochain;

·

Replace the principles of trustlessness with a

web of trust, i.e. integrate real human realtionships in trust-scaling

technologies;

·

Replace smart business contracts

with Ostrom contracts, that reflect the principles that govern the commons,

i.e. have smart contracts respect the ethical principles of a sustainable and

more socially just economy;

·

Replace competitive game incentives, based on

purely individual motivation and desire for gain, with cooperative game

mechanics;

·

Diminish the attraction and rewards of

extractive activities by rewarding generative activities, etc.

Figure 6 - Contrasting the

Propertarian Blockchain from Commons-Based Ledger Systems

Our

proposals reflect the conviction that we can tweak and transform the general

idea of the distributed ledger, to make it into a set of tools for production

for the common good. More importantly, even if we also want to use distributed

ledgers, the aim of their use is to recognize all contributions to the common

good and specific projects, not just commercial value recognized by the

capitalist market, and we want to recognize these and make them visible. Just

as importantly we aim to integrate the limits necessary to preserve our planet

and its multitude of beings for a long time, including a future for our

children and the next generations by making visible, in our distributed

accounting systems, the thermo-dynamic flows of matter and energy, creating a

context-based sustainability framework for all

participants in these networks.

Automating

some of these functions may help managing them. Expanding our capacity to

integrate commons-based, permissionless and passionate contributions in our

productive system, however, is equally important. Even as we want to create

ethical and generative livelihoods for all contributions, this does not mean

necessarily directly linking commons activities to market income. As we

explained above, the solution is to create a membrane which regulates the

relation between market and commons. This is of supreme importance if we want

to avoid a hyper-rationalisation of our behaviour and avoid a

transactionalisation of all aspects of life. We don’t want to subsume the

commons to the market and its logic, but to embed and subsume the market to the

necessities of human and non-human commons. By automating some of the aspects

of human cooperation, we want to create more space for non-market commoning.

And thus, despite these

limitations, and our critique of the current blockchain, the qualities and

advantages that the blockchain has brought into the world are of paramount

importance. What

matters is not just the flawed technology, but the patterns of thought and

interaction that it makes possible.

- First

of all, it has enabled the flow and exchange of crypto-assets and forms of

value, outside of the control of the existing and centralized financial

system. It is now possible to finance open source network infrastructures,

in ways that go beyond the prior dependency on the banking, payment, and

financial and venture capital based entities;

- This enabled a different line of thought

on value and money. Alternative value systems can be embedded in

currencies, as money is a social construct: imagined and designed by

humans.

While local complementary currencies have shown the potential for creating

local solutions, the new systems show that socially sovereign currencies

are scalable, and can be used by global virtual communities;

- Blockchain

economies subsume bounded firms to the logic of the network, based on the

use of open source commons and autonomously created monetary tools.

Corporations become co-dependent on multi-stakeholder networks and

commons;

- Token-based blockchain economies have the

potential to shift the balance of power between labor and capital. They

may allow a bigger part of the surplus value to flow to workers and other

stakeholders, avoiding domination by venture capital demand for an equity

stake;

The question is: will these

techniques, which favour a particular fraction of the labour aristocracy of

developers and technical-cognitive labour, also be applied for the wider commons

economy? Our position here is positive: all commoners can and must learn about

how this has been achieved, and whether it can be properly replicated

elsewhere.

The specific

design used in the creation of tokens is also paramount. Tokens allow for the expression

of multiple forms of value, which can eventually allow for the value

sovereignty we call for. The issuing of tokens for use as a medium of exchange

/ store of value within communities can be done in a way that incentivises

preferred behaviours and reinforces preferred values That is creating a direct

break of the dominant perception of money as commodity and opens up the

possibilities for other types of perceptions of value.

Most importantly, blockchains enable and ascribe the general

consensus on such subjective perceptions among communities, while facilitating

the interaction among them. Simply put, when a group of people agree that a

certain activity has merit, they can create a permanent and tamper-proof record

of this agreement. Let’s imagine for instance an energy cooperative building

small-scale wind-turbine. Its members may collaborate and create a set of rules

for the issue of tokens to engage more people in their cause (e.g. energy

engineers, households that want to reduce their dependence on fossil fuel,

etc.), and interact with other groups that may provide resources or support

services (e.g. a group of smart-grid experts, an impact finance firm, etc.).

Moreover,

crypto-tokens allow for crowdfunding or direct crowdsales, either through

utility tokens (a right to purchase the assets created by a blockchain project)

or through market-based tokens which allows stakeholders to partage in the

surplus value realized in the market. This allows founders, developers and

workers to go around the centralized banking and venture capital system,

finding their own funding more directly. These crowdfunding campaigns, based on

the sale of tokens that are open to all types of buyers, are called Initial

Coin Offerings.

Speculative ‘Initial Coin

Offerings’, can also be initial community offerings, as in the crowdfunding

campaign by Holochain. If the crowdfunding is successful, projects can go ahead

outside of the control of Venture Capital, which expects equity, i.e.

co-ownership, in return for its investments. By contrast tokens and Initial

Token Offerings, allows for the direct funding the workers, developers and

other stakeholders. If the project is successful and the token-price moves

upward, the work-related tokens rise in value, directly benefiting the workers,

who partake in the surplus value that was previously captured by the funders.

As Fred Ehrsam (2016), of

Coinbase expressed it:

So how do you get people to join a brand-new network? You give

people partial ownership of the network. Just like equity in a startup, it is

more valuable to join the network early because you get more ownership.

Decentralized applications do this by paying their contributors in their token.

And there is potential for that token (partial ownership of the network) to be

worth more in the future.

We believe that the

organization of a crypto-economy for the common good, based on enabling

commons-based peer production, which combines a recognition of a wider variety

of contributions, and helps achieve biocapacity accountability, will be based

on:

- a better integration of free and cooperative

mutual coordination, exchange and,

- the mobilization of resources through a fair and

generative ethical market, and,

- within a planning framework that reflects a

protection of planetary boundaries, and regulates access to the flows of

matter-energy to determine the bounds of usage through thresholds and

allocations of natural resources, as well as societal priorities.

Box 5 – Alternatives Distributed Ledger Technologies

|

Technology

|

Description

|

Applications

|

Characteristics/

Advantages

|

|

Tangle

|

A network data structure designed to

facilitate a range of secure transactions. To carry out a transaction you

need to validate two random previous ones.

|

IOTA: resource sharing platform for Internet of Things devices

|

+ no miners, no transaction fees

+ consensus mechanism embedded in

transactions

+ faster with more users

+ focused on machine-to-machine

communication

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ARVIDSSON,

A. Industrious modernity: On the future of digital capitalism. Available at: http://www.spui25.nl/spui25-en/events/events/2018/11/industrious-modernity-on-the-future-of-digital-capitalism.html.

access in: 05 dez. 2018.

ARRIGHI, G. Adam

Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the 21st Century. London: Verso,

2009.

BARBROOK,

R.; CAMERON, A. The Internet Revolution: From Dot-com Capitalism to

Cybernetic Communism. Amsterdam: Institute for Network Cultures, 2016. Available at: http://networkcultures.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/0585-INC_NN10-totaal-RGB.pdf.

Access in: 05 jan. 2018.

BARBROOK,

R. Cyber-Communism: How the Americans are Superseding Capitalism in Cyberspace.

Science as Culture, v. 9, n. 1, p. 5-40, 2000.

BAUWENS,

M.; NIAROS, V. Value in the Commons. Berlin:

Amsterdam: Heinrich Böll; P2P

Foundation, 2017a. Available at: http://commonstransition.org/value-commons-economy/.

Access in: 05 jan. 2018.

BAUWENS, M.; NIAROS, V.

Changing Societies Through Urban Commons Transitions. Berlin: Heinrich

Böll Foundation, 2017b. Available at:

http://commonstransition.org/changing-societies-through-urban-commons-transitions.

Access in: 12 jan. 2018.

BAUWENS, M.; NIAROS, V.

Changing Societies Through Urban Commons Transitions. Amsterdam: P2P

Foundation, 2016.

BAUWENS, M.; KOSTAKIS,

V. From the Communism of Capital to Capital for the Commons: Towards an Open

Co-operativism. Triple C, v. 12, n. 1, p. 356-361, 2014. Available at:

http://www.triple-c.at/index.php/tripleC/article/view/561. Access in: 05 jan. 2018.

BENKLER,

Y. The Penguin and the Leviathan: How Cooperation Triumphs over Self-Interest.

Yardley, PA: Crown,

2011.

BENKLER, Y. The

Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006.

BOCKMAN, J.; FISCHER,

A.; WOODRUFF, D. Socialist Accounting by Karl Polanyi: with preface “Socialism

and the embedded economy”. Theory and Society, v. 45, n. 5, p. 385-427,

2016.

BOTERO, G. Delle Cause della

Grandezza delle Cittá: A cura di Romain

Descendre.

Collana: Cliopoli, 5, 2016.

BURKE,

J. et al. Community Token Economies (CTE): Creating sustainable

digital token economies within open source communities. Amsterdam: P2P

foundation; Outlier Ventures, September 2017. Available at: https://gallery.mailchimp.com/65ae955d98e06dbd6fc737bf7/files/02455450-8a66-4004-965a-cf2f19fed237/Community_Token_Economy_Whitepaper_1.0.1_2017_09_01.pdf.

DAFERMOS, G. The Catalan Integral Cooperative: An

Organizational Study of a Post-capitalist Cooperative. Amsterdam:

P2P Foundation; Robin Hood Coop, 2017. Available at: https://p2pfoundation.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/The-Catalan-Integral-Cooperative.pdf.

Access in: 12 jan. 2018.

DARDOT,

P.; LAVAL, C. Commun: essai sur la revolution au XXIème siècle. Paris:

La Decouverte, 2014.

DE ANGELIS, M. Omnia

Sunt Communia: on the Commons and the Transformation to Postcapitalism.

London: Zed Books, 2017.

DUNN, C., GERARD, G.

J.; GRABSKI, S. V. Resources-Events-Agents Design Theory: A Revolutionary

Approach to Enterprise System Design. Communications of the Association for

Information Systems, v. 38, 2016.

ECONOMIC SPACE AGENCY. On

Intensive Self-Issuance: Economic Space Agency and the Space Platform. In:

GLOERICH, I.; LOVINK, G.; VRIES, P. (eds.) Moneylab Reader 2: Overcoming

the Hype, Institute of Network Cultures. 2018. p. 232-242.

EHRSAM,

F. Blockchain Tokens and the dawn of the Decentralized Business Model. In:

The Coinbase Blog. [S. l.], Aug 1, 2016. Available at: https://blog.coinbase.com/app-coins-and-the-dawn-of-the-decentralized-business-model-8b8c951e734f.

Access in: 14 jan. 2018.

EKBIA, H. R.; NARDI, B. A. Heteromation, and Other Stories of

Computing and Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017.

ELKINGTON, J. Towards

the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable

Development. California Management Review, v. 36, n. 2, p. 90–100, 1994.

FERNÁNDEZ, R. V. The

pattern of socio-ecological systems: a focus on energy, human activity,

value added and material products. Thesis (Doctoral). 2017. [Barcelona]: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona,

2017. Available at: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/187290?ln=en.

Access in: 05 jan. 2018.

FOTI,

A. General Theory of the Precariat: Great Recession, Revolution, Reaction.

Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2017.

FUGGER, R. Money as IOUs in Social

Trust Networks & A Proposal for a Decentralized Currency Network Protocol. April

18, 2004.

Available at: http://archive.ripple-project.org/decentralizedcurrency.pdf.

Access in: 05 jan. 2018.

GIAMPIETRO, M.; MAYUMI,

K. Multiple-Scale Integrated Assessment of Societal Metabolism: Introducing the

Approach. Population and the Environment, v. 22, n. 2, p. 109-153, 2000.

GLEESON-WHITE, J. Double

Entry: How the Merchants of Venice Created Modern Finance. New York: W.W.

Norton & Company, 2013.

HAUGEN, R.; MCCARTHY,

W. EREA: A semantic model for internet supply chain collaboration. ACM

CONFERENCE ON OBJECT-ORIENTED PROGRAMMING, SYSTEMS, LANGUAGES, AND

APPLICATIONS, 21, January 2000, Minneapolis. Available at:

http://jeffsutherland.org/oopsla2000/mccarthy/mccarthy.htm. Access in: 10 jan. 2018.

KELLY, M. Owning Our

Future: The Emerging Ownership Revolution - Journeys to a Generative

Economy. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2012.

LE GOFF, J. La

naissance du Purgatoire. Paris: Gallimard,

1981.

MANSKI,

S.; MANSKI, B. No Gods, No Masters, No Coders? The

Future

of Sovereignty in a Blockchain World.

Law Critique, v. 29, p. 151–162, 2018.

MARSH, L.; ONOF, C.

Stigmergic Epistemology, Stigmergic Cognition. Cognitive Systems Research,

v. 9, n. 1-2, p. 136-149, 2007.

MCCARTHY, W. E.

Construction and use of integrated accounting systems with entity-relationship

modeling. In: CHEN, P. (ed.) Entity-relationship approach to systems

analysis and design. Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing Company, 1980. p.

625-637.

MCCARTHY,

W. E. The REA accounting model: A generalized framework for accounting systems

in a shared data environment. The Accounting Review, v. 57, n. 3, p. 554-578,

1982.

MOTESHARREI,

S.; RIVAS, J.; KALNAY, E. Human and nature dynamics (HANDY):

Modeling inequality and use of resources in the collapse or sustainability of

societies. Ecological

Economics,

v. 101, p. 90–102, 2014.

PAZAITIS,

A.; DE FILIPPI, P.; KOSTAKIS, V. Blockchain and value systems in the sharing

economy: The illustrative case of Backfeed. Technological Forecasting &

Social Change, v. 125, p. 105-115, 2017a.

PEREZ,

C. Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of

Bubbles and Golden Ages. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Pub. 2002.

POLANYI,

K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of our

Time. Boston: Beacon Press, 1957.

PORTER,

M. E. Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a

Global Economy. Economic Development Quarterly, v. 14, n. 1, p. 15-34, 2000.

PORTER,

M. E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations. New York: Free Press. 1990.

RAMOS,

J. Cosmo-localization and leadership for the future. Journal of Futures

Studies, v. 21, n. 4, p. 65-84, 2017.

RAWORTH,

K. The Doughnut Economics: 7 Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist.

Harford, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018.

SANGSTER,

A. Using accounting history and Luca Pacioli to put relevance back into the

teaching of double entry. Accounting, Business & Financial History,

v. 20, 1, p. 23-39, 2010.

SOMBART,

W. Der Moderne Kapitalismus, Bd. 1: Die Genesis des Kapitalismus.

Leipzig: Duncker & Humbolt, 1902.

SPUFFORD, P. Power and Profit: The

Merchant in Medieval Europe. London:

Thames & Hudson, 2002.

STANDING,

G. The Precariat: The new dangerous class. Broadway: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011.

TEECE,

D. Competition, cooperation and innovation: organisational arrangements for

regimes of rapid technological progress. Journal of Economic Behaviour and

Organisation, v. 18, n. 1, p. 1-25, 1992.

VANDENBOSSCHE,

P. E. A.; WORTMANN, J. C. Why accounting data models from research are not

incorporated in ERP systems. INTERNATIONAL REA TECHNOLOGY WORKSHOP, 2., 25

June, Santorini Island, 2006. p. 4-30.

WHITAKER,

M. D. Ecological Revolution: The Political Origins of Environmental

Degradation and the Environmental Origins of Axial Religions; China, Japan,

Europe. Available at: https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Political_Origins_of_Environmental_Degradation_and_the_Environmental_Origins_of_Axial_Religions. Access In: 05 jan. 2018.